Human Innovation Series: Flight for All

The Wright Brothers flew first. Amelia Earhart flew famously. But Glenn Curtiss? He made sure we could all fly. While others chased records or recognition, Curtiss built schools, taught thousands, and proved the sky wasn’t reserved for the elite. He turned flight into a shared future.

Glenn Curtiss grew up in the small Finger Lakes town of Hammondsport, New York. He left school in eighth grade and built bicycles and motorcycles in his hometown garage. In 1907, that garage became the launchpad for a new era of motion. He bolted a V8 engine to a bike frame and shattered the land speed record, becoming the fastest man on Earth, clocking 136 miles per hour on his homemade bike.

Glenn Curtiss on his V-8 motorcycle, Ormond Beach, Florida, in January 1906.

But his sights were always set higher. What if humans could move through the sky with that same speed, control, and freedom?

In 1908, Curtiss built and flew the June Bug, an aircraft with an 8-cylinder engine. The Wright Brothers did make the first powered flight in 1903, but they were intensely secretive. For years, they focused on securing patents and partnerships and their flights were often hidden from the public and the press, which left many to wonder if powered flight was real at all.

The June Bug was an early aircraft designed by Glenn Curtiss.

Unlike the Wright Brothers, Curtiss did something radical: he invited people to watch. He announced the flight, welcomed observers, and allowed the press to report every detail. When the June Bug lifted off and flew over 5,000 feet in front of hundreds of witnesses, it wasn’t just a technological triumph, it was a cultural one. It wasn’t the first flight ever, but it was the first flight most people believed and saw. That’s why his flight won the Scientific American Trophy, and why the press hailed it as the moment flight became real for the people.

Glenn Curtiss in His Bi-Plane, July 4, 1908, gelatin silver print.

Curtiss believed aviation shouldn’t be reserved for the elite or the lucky few. He developed the first seaplane, making flight possible wherever there was water, not just land.

Perhaps Curtiss’ most lasting impact came not from what he built, but who he taught. He built a network of schools that welcomed people of all genders, nationalities, and abilities. One of his students, Blanche Stuart Scott, would become the first American woman to fly solo in 1910, nearly two decades before Earhart’s Atlantic crossing.

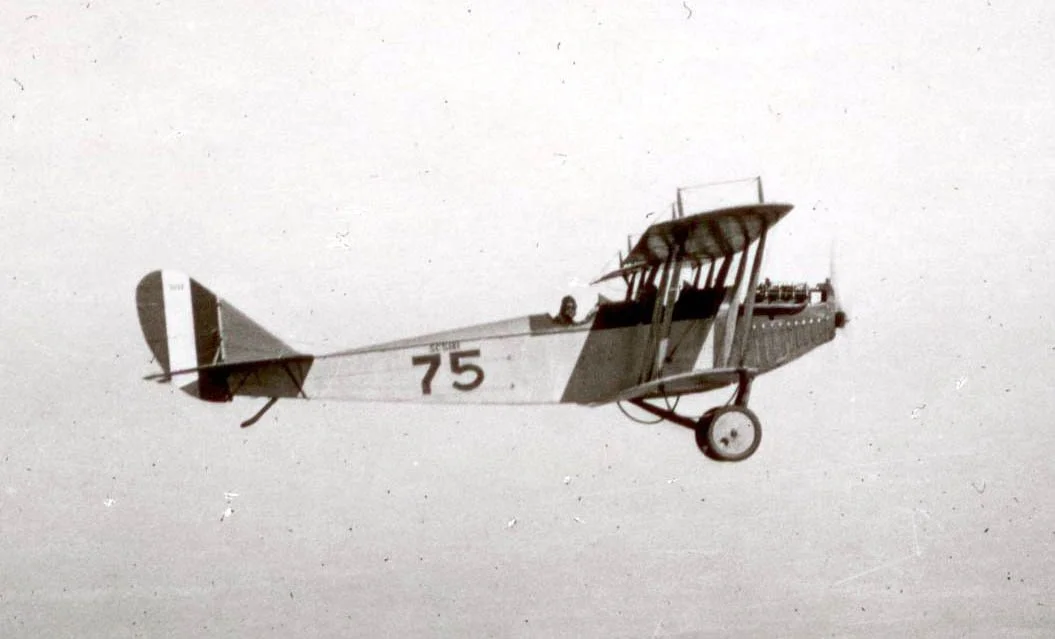

Newspapers called his schools a “wonder of the century.” He designed the Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny,” a training aircraft so accessible and reliable that 95% of American and Canadian pilots in World War I learned to fly using it.

A Curtiss JN-4 (Jenny) on a training flight during World War I.

Curtiss's influence stretched far beyond his own machines. His open-door approach to aviation seeded an entire aviation ecosystem: schools, instructors, tools, and infrastructure. He taught the world not only how to fly, but how to teach flying.

In 2003, Glenn Curtiss was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. He is considered the most influential man in the evolution of aviation. But his greatest genius may have been his belief that flight belonged to everyone.

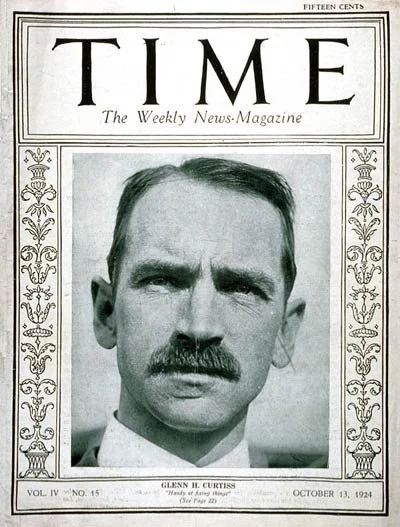

1924 TIME Magazine Cover featuring Glenn Curtiss

You may never have heard his name. But you live in the world he made possible.

At Think Variant, stories like this remind us that innovation matters most when it’s shared.

Because when you democratize the future, the whole world moves forward.