Human Innovation Stories: Teaching The World To Fly

Sometimes innovation doesn’t begin with expensive equipment or millions of dollars. Sometimes, it begins in humble places, like a piano shop.

This is a story about ingenuity, perseverance, and a man who taught the world to fly.

Edwin Link was fascinated by the sky and flew for the first time when he was 16 years old. He devoted his time between flying and working at his father’s piano and organ factory in Binghamton, New York. Link knew that there had to be a safer, more accessible way to teach young pilots how to fly without throwing them straight into a cockpit with no training.

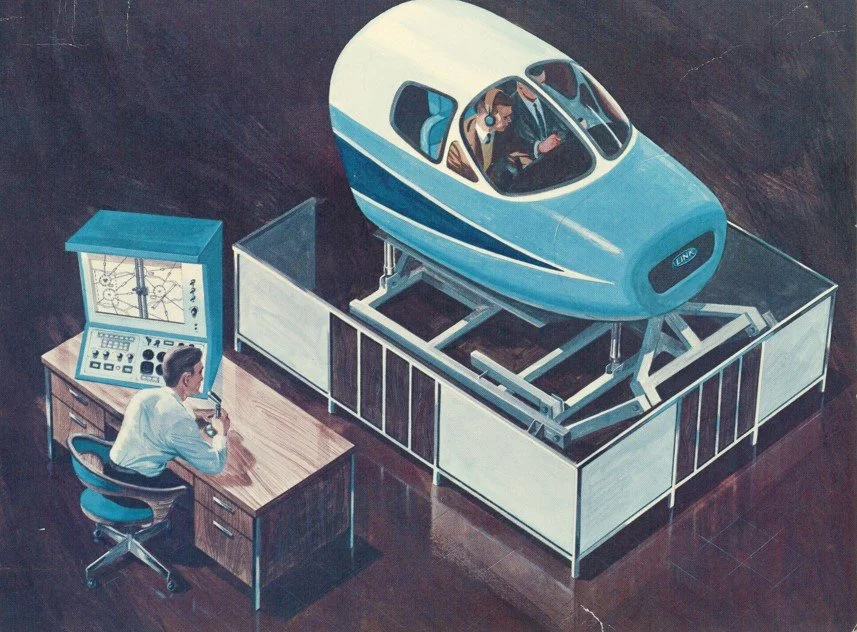

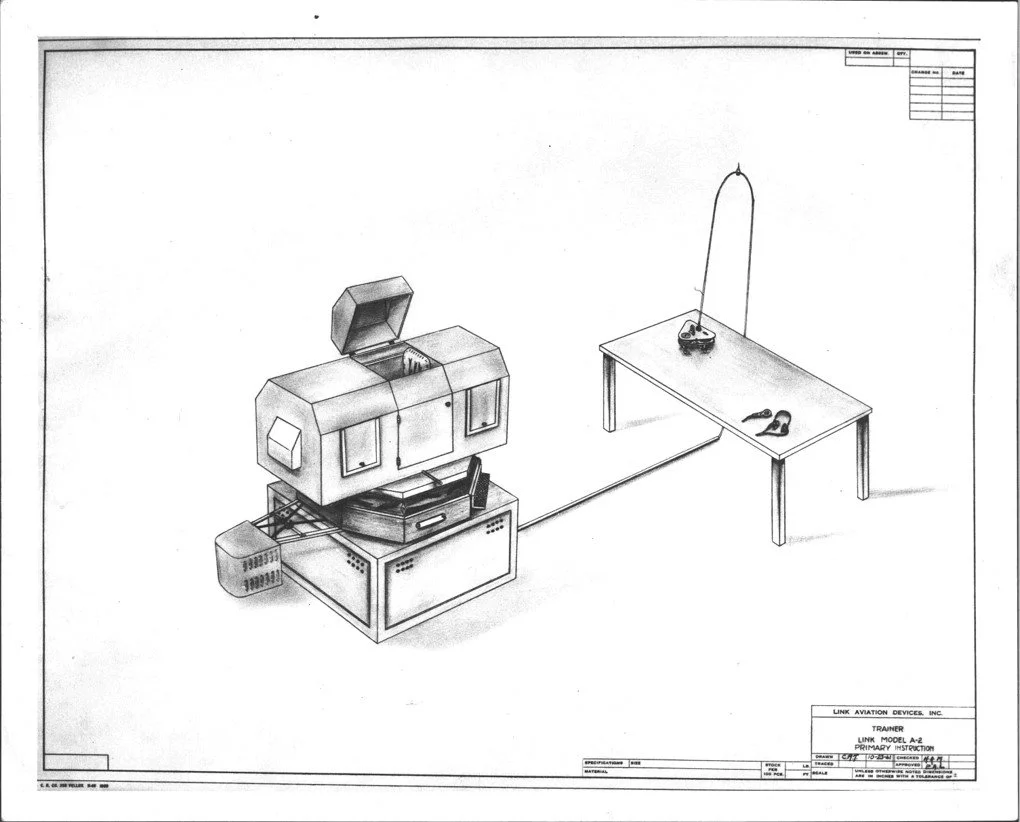

He took the tools he knew, bellows, air pumps, valves, and reimagined them. After nearly 18 months, he had assembled them into something no one had seen before: a wooden cockpit on a jointed base. This was a machine that could pitch, tilt, and respond to real flight controls. It could mimic storms and disorientation, all before computers and the internet.

He called it the Link Trainer. It was the world’s first flight simulator.

At first, no one in aviation took it seriously. Only amusement parks were interested. Early models were painted red and blue and became coin-operated rides that shook and spun.

But Edwin didn’t give up.

In the early 1930s, pilots flying airmail routes were dying, not because of bad planes, but because they didn’t know how to fly in low-visibility conditions. In just 78 days, twelve pilots were lost in fog and storms. The Army Air Corps started looking for solutions.

In 1934, Edwin flew into a military meeting in conditions so foggy the generals thought flight was impossible. He landed safely. When they asked how, he pointed to his machine: he had trained for it.

That day, the Army ordered six Link Trainers.

By World War II, more than 500,000 Allied pilots had trained on the mechanical box built by piano pieces. It became a quiet hero of aviation, a machine that didn’t fly, but taught people how to survive in the sky.

Today, every pilot, astronaut, surgeon, and rescue worker who trains in a simulator is guided by a legacy that began with bellows and a belief.

Edwin Link was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1976. And Syracuse University’s College of Engineering now bears his name.

At Think Variant, stories like this remind us that world-changing ideas don’t always begin with giant corporations or massive funding. Sometimes they begin with a conviction that there is a better way and the will to build it.

The Link Trainer didn’t just prepare pilots. It launched a whole new way to learn. It redefined how humans learn under pressure. Simulators now train astronauts, surgeons, and rescue teams around the world, all because one person got to work.

So here’s our question to you: What would you build if you stopped waiting for permission?