Building Syracuse Together

At the turn of the twentieth century, Syracuse, New York was booming. It was a city alive with creators and innovators who believed that ingenuity and craftsmanship could drive progress. Few American cities brought together art, design, architecture, and industry in such a practical, visible way.

Archimedes Russell

Architect Archimedes Russell reshaped the skyline with buildings like the Hall of Languages and Crouse College, sturdy, detailed buildings of stone and brick, designed to last for generations. Russell’s work reflected what the community valued: education, art, and craftsmanship.

Hall of Languages, circa 1876

Architect Archimedes Russell

Gustav Stickley

Just a few streets away, Gustav Stickley was redefining American furniture as a reflection of moral and material integrity, rejecting excess in favor of solid oak, visible joinery, and the beauty of honest work.

Gustav Stickley

Stickley Furniture, circa 1902

James Pass

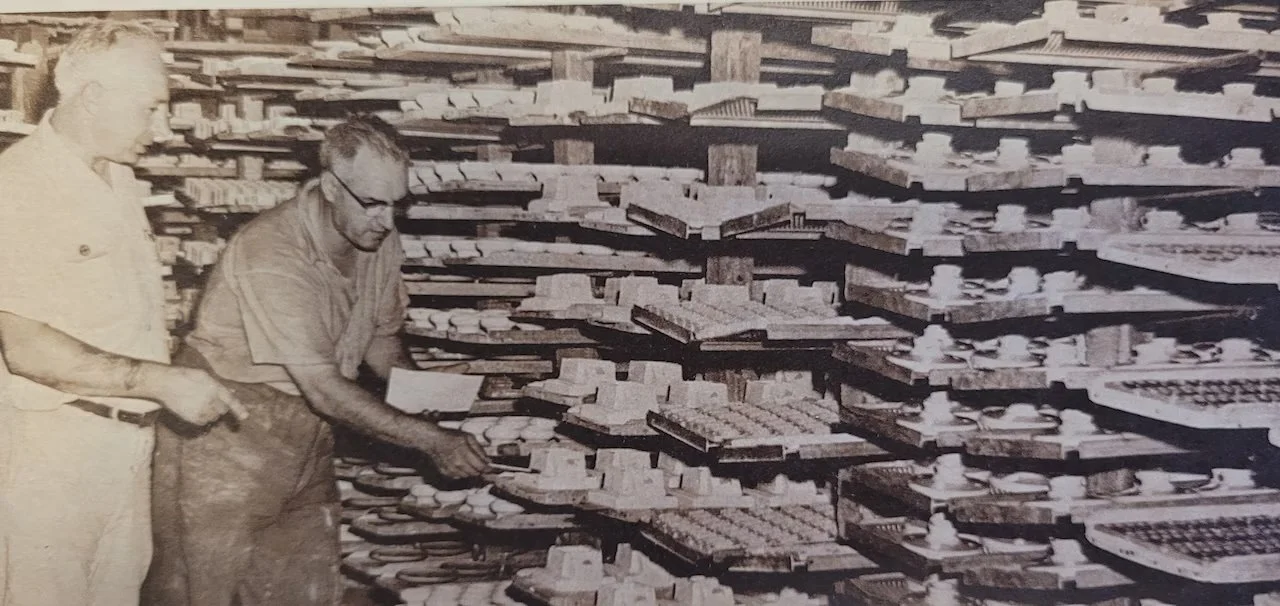

In the factories, James Pass, president of the Onondaga Pottery Company (Syracuse China), was revolutionizing porcelain.

He developed a new clay body, stronger, denser, and with a cleaner, brighter finish, setting a new industry standard that made the company a national leader.

Syracuse China contributed to electricity’s growth in America

Adelaide Robineau

Amid this surge of invention, largely led by men, a woman stood out.

Adelaide Alsop Robineau refused to within the limits set for her. When most women were confined to painting decoration on someone else’s porcelain, she broke from tradition. She mixed her own clay, threw her own forms, and created new glazes, work that, at that time, only men were permitted to do.

But Robineau didn’t stop there. She did more than master her craft or defy expectations, she built community. She believed knowledge should be shared, not kept to herself.

Adelaide Robineau, working on the Scarab Vase

Keramic Studio Magazine, 1899. Created by Anna Leonard and Adelaide Robineau

Through her magazine, Keramic Studio, she shared her experiments and formulas, her failures as openly as her discoveries, and wrote about how beauty and function intertwine, how ideas evolve when they’re shared.

She invited her readers to experiment and to collaborate, to see craft not as competition, but as conversation. In doing so, she democratized porcelain, transforming it from a guarded tradition into a shared pursuit of excellence.

Together, Defined American Arts & Crafts Movement

James Pass, president of Syracuse China, took notice and invited her to consult and collaborate, recognizing Robineau as a peer who blurred the lines between art and industry. Pass’s experiments in porcelain eventually reached far beyond the dinner table, evolving into the electrical insulators and ceramic components that powered modern life.

Together, ceramist Adelaide Robineau, industrialist James Pass, furniture maker Gustav Stickley, and architect Archimedes Russell, shaped more than objects; they built a culture of collaboration that helped define the American Arts and Crafts movement. Their innovations emerged not from isolation, but from conversation and curiosity.

A century later, that spirit still breathes in Syracuse. The city remains a hub of ingenuity: a place where inventors, architects, engineers, and artists continue to cross boundaries and share ideas.

Syracuse, Now

Whether you’re building drones, developing new materials, or designing new tools, the lesson is the same: innovation doesn’t happen in isolation, collaboration matters. It happens when we open our experiments, share our stories, and invite others into the process.

Syracuse’s past reminds us that innovation grows not from competition but from connection. Progress is a conversation, one you can join.

Share your experiments, talk across disciplines, and open up your work. That’s how innovation evolves.